Directed by Vasilis Katsoupis and written by Ben Hopkins, Universal Pictures' Inside presents a portrait of mystery and behavioral complexity. That it's helmed by the great Willem Dafoe only helps stir its tart, claustrophobic flavor.

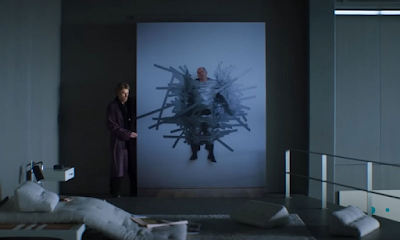

Dafoe is an artist and art thief named Nemo, placed in a New York high-rise for a heist of multimillion-dollar paintings, but the break-in goes awry with a malfunctioning alarm system. Interestingly enough, though the system locks him in, it doesn't alert outside forces, making him prey to what's inside: some imagined, some real.

With that said, it's often hard to unravel Nemo's caged predicament. As he tries to pry himself out of the apartment, the temperature rises, and the spigot water slows to a trickle. Though he catches oblivious folks on the security monitors (a kind of Rear Window deal, but with much less to view) and engages in lofty reveries (highlighted by Gene Bervoet and Ava Van Voigt, a philosophizing rich man and his daughter, who Nemo hopes to outwit), his despair widens, while Eliza Stuyck's attractive cleaning lady becomes his frequent, fruitless distraction: a dangling carrot he just can't seem to nudge.

Not to spoil anything, but the arduous journey culminates in an abstract turn, which begins to enter the plot about halfway through, but it's the entire trip, not the mere ending, that matters here. All the same, Inside's revelation mixes defiance with defeat, creating nothing less than an elevated Hell on Earth. Then again, isn't Hell (in addition to all matters of "creation and destruction", as Nemo states), a consequence of artistic endeavor?

In its later sections, Inside feels like a modernized Robinson Crusoe, though with no Friday or Spalding, or Silent Running without the endearing drones. It also invokes Rod Serling's Twilight Zone pilot, "Where is Everybody?", his Night Gallery parable, "Escape Route", Stephen King's The Shining (in particular Stanley Kubrick's redesign of it) and Poe's The Premature Burial, which essays the varied ways some(body) might survive (or not) in a symbolic box. It would work as a one-man play, and for the most part, it's just that, albeit caught on film and sometimes sprayed in Creepshow hues, but any such exercise is only as good as its lead, and this one flaunts one of the best.

As Nemo, Dafoe is confused, haggard, intense and for survival's sake, damn rubbery. We know he's done wrong, but because we share his prison term, we embrace his plight. His liberation could become ours, and on an allegorical track, any such deliverance could break us from, let's say, a suffocating job or rotten relationship: anything that we might find shackling and cursed by no recourse.

Inside still haunts me, instilling a gnawing empathy that's difficult to shed. It's that part of Nemo's melancholia that I wish to keep, for I've learned much about myself from it, and from the story's cerebral seepage, I'm certain there's even more I'll come to consider.

No comments:

Post a Comment