Benson's extensive discourse elevates the film's creators (men who shared an insatiable urge to probe, experiment and discover), for without director Kubrick and author Clarke, the abstract, interpretive installment would have never reach fruition, let alone remain a cinematic example that connoisseurs still dissect, debate and savor. To support his stance, Benson offers biographical overviews on both men, but singles out their artistic impulses and worldly knowledge as the cause of "2001'"s longevity.

For many, the film (derived in part from Clarke's short story, "The Sentinel") is a subjective and oblique experience. Benson's reflection on this matter furthers this view, as he recalls seeing the film as a youth and then in later years when he absorbed its celestial depth with greater, personal insight. However, to get to the latter, an understanding of the making-of fundamentals is required.

At the book's outset, Benson attributes a basic purpose to Kubrick and Clarke's partnership, stating that "2001", like James Joyce's "Ulysses", surfaced as a lofty refashioning of Homer's "The Odyssey". Where Joyce's version condensed Homer's tale to a day, Kubrick and Clarke's expanded it to four million years of human evolution, marked by one scene-jarring jump. (In actuality, Clarke had tested the human-progression concept in his novel, "Childhood's End", but via Kubrick's deft handling, "2001" shuttles it per optical and musical means akin to Walt Disney's "Fantasia".)

To promote the resounding, Homerian link, Benson reminds us that "2001'"s protagonist, Commander Dave Bowman (Kier Dullea) acts in lieu of the legendary Ulyssess/Odysseus. In this respect (and if only through the creators' incidental intent), the spaceman's surname alludes to the adventurer's slaying of Penelope's suitors via bow and arrow. Benson further explains that Discovery's computer, HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain) performs as Bowman's Cyclopian antagonist and the monoliths, understudies for Greek gods.

Benson's Greek-god referencing made me recall how I took the monoliths as symbolic slates upon which the viewer might transpose any number of ideas. Indeed, the formations might be, as the author asserts, alien communicative devices, or as I fancy, God teleporting from one omnipotent station to another to grant humankind its rise to Star Child status. (This transformation would only occur if humankind proved worthy of progression, whether through a weapon, music...a space vessel: God only helps those who help themselves.)

The Homerian springboard inspires the reader to consider an array of intrinsic vantages, despite the specific goal employed. As with Patrick McGoohan's cryptic sensation, "The Prisoner" and David Lynch's eerie excursion, "Eraserhead", Kubrick and Clarke had, in fact, paved a narrative path, but kept their odyssey open for scrutiny and revision as the production extended. This in turn has nurtured the movie's significance, no matter the decade or context in which it's viewed.

Benson references the movie's purposeful, though contradictory styles to help one understand its ambivalent ascent (both on and off screen). For example, to swing from "ape to angel", both primitive and stellar landscapes were employed. Benson identifies the former's austerity, but also respects (and inspects) what thereafter became the film's credible, technical allure.

A major part of that allure is HAL: an entity that's as much Frankenstein Monster as Polyphemus. Bowman's battle with HAL (the explorer's right of passage in God's eye, as I prefer to see it) is what ushers the astronaut toward humankind's next phase. It's understandable, therefore, why Benson references HAL throughout his text, since Kubrick and Clarke (whether by accident or plan) did the same, perhaps only to adhere to the epic's pervading evolutionary and mythic motifs.

Benson focuses as well on the movie's meticulous construction through its narrative, supplemental and obstructing forms: all of which were spurred, to some extent or another, by its creators.

To demonstrate this, Benson's production roster ranges from financial constraints; plot shifts; reshoots; hallucinogenic supplements; the Dawn of Man location hunt; Stuart Freeborn's simian suits; Douglas Trumbull's awe-inspiring effects; music choices; behind-the-scenes disputes (particularly between Kubrick and Clarke); the film's unconventional length (making it an inflated "Destination Moon" of sorts); and critical reception.

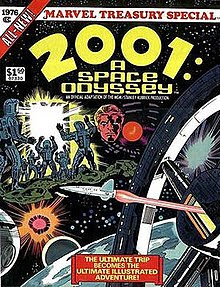

Benson admits that "2001" wasn't embraced at initial showings, neither by MGM highbrows or mainstream critics, though was thereafter championed by a growing, global counterculture. In addition, Benson explains how "2001" further dispelled its critical derision by becoming a pop-cultural phenomenon, with literary, cinematic and illustrated sequels. (Evident influences of "2001" {though not all cited by Benson} are found in John Carpenter's "Dark Star"; Andrei Tarkovsky's "Solaris"; Gerry Anderson's "Space: 1999"; Robert Wise's "Star Trek--the Motion Picture"{a variant of Wise's "Run Silent Run Deep"}; and if one is perceptive enough, Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind"; Stanley Donen's "Saturn 3"; James Cameron's "The Abyss"; Alex Proyas' "Knowing"; and Christopher Nolan's "Interstellar". Benson includes David Bowie's "Space Oddity" as an embraced reply to Kubrick and Clarke's vision.)

Benson's vast, scrupulous survey convinces us why "2001" remains relevant beyond the titular year that should have antiquated it. Benson implies that it's not so much the film's stunning hardware that makes it significant, but its human core: ironic since the production has been criticized for being cold and assiduous, but aren't such raw elements the catalyst behind any human achievement? Benson, therefore, conveys that it's the rough forging of ideas, that reaching beyond reasonable limitations, which allows humankind to progress, if not physically, then mentally...spiritually.

Benson renewed my position that Kubrick and Clarke's allegory reintroduces our emanation so that we might see how far we've grown as species and how far we're yet to go, with both good and bad attributes attached along the developmental track. Whether this process quickens per some ethereal push doesn't matter as much as humankind's tenacious drive for the leap.

Benson's drive (his monumental research) has resulted in comparable greatness. Through the movie and its benefactors, Benson inspires readers to believe that they, too, can seize prestigious goals. For any "2001"/Kubrick/Clarke fan, Benson's work is an indispensable reference tool and in an unorthodox way, an inadvertent, self-improvement source.

I also recommend the audio edition of Benson's book, as performed by Todd McLaren, whose affable tonality does the subject justice. (He also does a pretty cool Carl Sagan.)

Print and audio editions of "Space Odyssey..." can be purchased through Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other fine, literary outlets.

http://www.artslettersandnumbers.com/1/people/michael-benson

ReplyDelete